I wrote this piece in 2003, but want to share it with you now on the occasion of the fiftieth anniversary of the Chicano Moratorium. In this time of the Covid crisis, the upsurge of the Black Freedom Struggle, and the Trump Administration’s effort to ethnically cleanse the US of more than 11 million undocumented migrants, the great majority of whom are Latin@, we can learn lessons from our history that can help inspire and guide us through the treacherous political waters in which we are currently immersed.

Bill Gallegos

August 2020

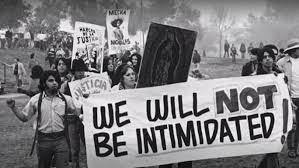

Reflections on the past are always a tricky endeavor. It is always best to proceed with the admonition to separate nostalgia from history. It has been thirty-three years since the great Chicano Moratorium Against the War, when more than 25,000 gente marched through the heart of East LA (or maybe the soul of Aztlán) in opposition to the American War of aggression against Vietnam, the war that the Vietnamese people call the barbaric aggression the United States waged against them.

It is fairly well known that the march was a protest against the excessive casualty rate suffered by Chicano troops in the US military, that the march was attacked by a massive police force that wounded hundreds and murdered four of the marchers, including journalist Ruben Salazar. Up until the great Los Angeles March Against Proposition 187 in 1994, the Moratorium was the largest mass action in Chican@ history. Gracias to all those who keep the flame of this important memory alive with commemorations, teatros, spoken word, and mass actions.

For my part, I want to share my thoughts on the significance of the Moratorium from a perspective slightly different from that we usually hear. I dedicate these thoughts to Larry Amaya, a Chicano veteran, activist, and working-class intellectual who worked for years, ultimately successfully, to convince the GI Forum to oppose the US war against Viet Nam. I believe they were the first, and possibly only mainstream veterans’ organization to do so. Larry died several years ago, but remains an inspiration to all who knew him.

As a Chicano who came of political age during the time of the Moratorium, I celebrate it because it revealed, in a way that could not be denied by the powers-that-be, that the revolutionary and radical sector of our movement had a genuine and important mass following. Part of the self-conscious definition of Chican@ revolutionaries was being an alternative to the mainstream forces (políticos and others) grouped around the Democratic Party and that generally supported the status quo, although advocating for limited reforms of that system.

Most of them refused to condemn the US war in Viet Nam. But by the time of the Moratorium, radical organizations like the Crusade for Justice, the Black Berets, La Raza Unida Party, and the Brown Berets challenged the often passive or accommodationist views and policies of mainstream Chicanos. (Gracias a diós, few used the term Hispanic back in those days.) While many of us probably tossed around the term “vendido” a little too loosely in reference to these forces, there was a lot of truth to the fact that the mainstreamers advocated a tired, liberal integrationist road to social equality, and worked hard to contain within proscribed political limits the mass rage and mass action of our people. They hoped to reassure the establishment that the radicals had no real following among the people, and that these políticos were our genuine “leaders”.

The truly mass character of the Chicano Moratorium, organized and led by outspoken revolutionaries, shot that hot air balloon right out of the political sky.

The Moratorium was more than a slap in the face to the reformists, it was truly a festival of our working class–of the folks who make up the overwhelming majority of our people. The Moratorium was broad–it included many sectors of our community–youth, students, middle class, professionals, artists, elders, etc. But its ranks were filled mainly with folks whose shirt collar was blue, whose hands were calloused from hard work. Their participation gave a special importance to the Moratorium because it showed the world that the majority of our people were against, or were developing opposition to the US war.

More than 25,000 marching feet gave evidence, more powerful than any Gallop poll, that Chican@s were not blind patriots driven by the need to prove our “right” to reside in the US by fighting its wars. Internal memos from the Nixon Administration reveal that President Nixon himself was totally freaked by the Moratorium because he and the ruling class generally had assumed Chican@’s support for their foreign policy (including efforts to destroy the Cuban Revolution). His racist administration expected opposition from Blacks, but from Mexicans–please!

There is much talk these days about empire and imperialism. Even bourgeois pundits use the term fairly casually. Back in the day though, these were terms and concepts with currency mainly among the left and revolutionary sectors. I love the fact that the Chicano Moratorium’s slogan, signs and chants were an open declaration of war against empire: “Nuestra Guerra Es Aqui” is a hellacious grito; it is an unmistakable statement with an internationalist significance. The Moratorium did not identify with the US empire, but with the Vietnamese freedom fighters who were kicking the hell out of the most powerful war machine in the world. This slogan, and others that expressed open support for the Vietnamese, also identified our struggle as a struggle for NATIONAL LIBERATION, not simply for a “piece of the pie” (i.e. elected officials, academics, entry into the corporate sector, etc.).

While earlier actions (such as the 1969 Chicano Youth Conference) made similar declarations, the Moratorium showed mass support for what had been primarily a manifesto of activists. The Moratorium placed the Chican@ Liberation Struggle clearly and unequivocally within the ranks of the anti-imperialist struggles of Southeast Asia, of the Cuban revolution, of the national liberation movements in Africa and Latin America.

Those were heady times my friends. Many of you may have clearer recollections and deeper reflections about the Moratorium than my own, but I wanted to share these thoughts with you. Because you ARE my friends, my colleagues, and my fellow activists in our grand endeavor to end all oppression, exploitation, and inequality.