The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project 2-3

January 20, 2021/ This week’s issue/ Meizhu Lui, for the editorial team

Two weeks ago, mob violence erupted at the US Capitol and left five dead. We live in violent times. Children shot in their schools. Police murdering Black folks in city after city, White supremacists shooting Jewish and Black worshipers. The remains of migrant families found baking in the desert, other bodies found floating in the Rio Grande.

In México, violence also fills the daily diet. Students disappeared. Drug wars rife with torture and random killings. Political murders of journalists and politicians. Women dismembered and skinned just for being women.

The numbers mount, the atrocities multiply, and after awhile, our eyes glaze over. The statistics put a distance between us and the dead. We move on to the sports page.

But there are actual bodies matching the numbers. And there are those who deal with the corporal reality: people who mop up the blood, look for bone fragments in the dirt, examine wounds on the dead body for signs of torture or struggle, draw out bodily fluids with syringes. After seeing, smelling, touching what used to be a person who had a mother, co-workers, a life; perhaps talking with those who loved that person, what do you do with that intimacy? Where do you put it?

In our interview this week, we hear about two people who have handled bodily evidence of violence, and they put “it” into art. They can’t forget, and they don’t want us to forget the people who’ve been lost.

Can we imagine a world free from the fear of violence? At this historical juncture with greater violence or greater peace in the balance, we must be determined to make that new world your world, my world, our world.

| Leonard Correa worked for years as a crime scene investigator in Southern California, taking photographs of victims and the places where crimes befell them. He would turn, over time, to personal photography as a way to deal with his inability to forget the tragic events he was documenting. On one assignment, Correa found that his own cousin had been shot to death. His gripping photographs have now appeared widely in art exhibitions. |

The earth also was corrupt before God, and the earth was filled with violence. Genesis 6:11

| You and the Mexican artist Teresa Margolles both had jobs involving those who died violently. How did those experiences affect you and Margolles? Leonard Correa: As a former crime scene investigator, I witnessed the sheer and unimaginable brutality one human can inflict upon another. Many of the crime scenes left a lasting impression on my consciousness, and those ordinary streets and buildings I often had to keep passing became visual reminders of the traumatic event that took place there. The rest of the world moved on. I could not “unsee” and had to deal with these triggers. The Mexican artist Teresa Margolles has witnessed the results from acts of inhumanity tenfold. She worked as a forensic pathologist in México during the “drug wars.” Many of us carry the burden of these images of violence in silence. Margolles rejects that silence. She chooses to incorporate the biological remnants of the victims into her sculptures. Blood and tissue from dead bodies become an inescapable element of her art. |

Margolles has a particular focus on the murders of women, is that right?

| Yes, she’s titled one of these powerful works Lote Bravo. It is a series of earthen, adobe-like blocks made from the dirt from various locations surrounding Ciudad Juarez, places where hundreds of innocent women endured the horrors of rape and murder before being discarded by their captors like toys that no longer interested a child. These blocks may seem innocuous to the viewer, but, in context, they become a visual testimony to victims and crimes many have forgotten. The blocks provide the viewer with a sense of the pain and suffering the earth has absorbed from the victims, like a mother embracing a dying child in her arms. Margolles eases Mother Earth’s burden by sympathetically removing the soil from her arms to create these blocks so that the spirits of those taken can make an indelible mark on the consciousness of the viewer. |

Besides Lote Bravo, what other works by Teresa Margolles speak to you as someone who also frequented crime scenes?

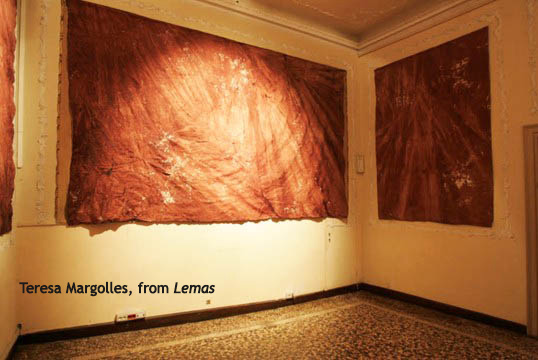

Her use of cloths infused with the blood of victims following the autopsy procedure makes Lemas another forceful series. At first glance, the random patterns may seem as intriguing as the Shroud of Turin. But as the viewer gets drawn in, the smell and the texture of the dried blood strikes the senses with the grim reality of a life lost to violence.

| As an artist yourself, do you think these pieces by Teresa Margolles are meant simply to honor the unnamed dead? |

I feel that these pieces serve a dual purposes. In communities constantly exposed to violent crime, people quickly become desensitized to the plight of others. And those who only read about the violence in the local papers, or see it on the nightly news, can all too often become indifferent to these horrors. Teresa Margolles forces us to confront the material reality of death, she wants all of us to be unable to forget, to know we have a moral obligation to speak out against these crimes. Her art calls us to action.

Across the world, women are being murdered. Femicide — getting killed because you are a woman or a girl — has become a particularly brutal reality in both the US and México. Both countries are also witnessing growing movements that are demanding an end to gender-based violence. These movements are organizing to bring those who have died back into our fold. They won’t allow these dead to be trivialized, blamed, or forgotten. Just as Teresa Margolles uses visual art as a tool for justice, Alysia Lee uses music. An African American singer, composer, and founder of a girls’ empowerment choral academy, her powerful composition Say Her Name calls us to conscience. Listen.

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media,

on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border

Kurt Hackbarth, The Mexican Right Has United to Defeat AMLO, Jacobin. The midterm election campaign has just kicked off, and President López Obrador’s opponents have formed a coalition against his party. Their aim: to seize a lower-house majority and stop AMLO’s progressive agenda.

Cameron Peters, What Biden wants to do on immigration, briefly explained, Vox. Biden’s immigration plan includes a pathway to citizenship, but faces an uncertain future in Congress.

Natalie Kitroeff, Alan Feuer and Oscar Lopez, In Blow to U.S. Alliance, Mexico Clears General Accused of Drug Trafficking, New York Times. The Biden administration will need to rebuild drug-enforcement cooperation after Mexico discounts U.S. evidence that Gen. Salvador Cienfuegos worked for a cartel.

México moves to create world’s largest legal cannabis market, Reuters. Reforms would allow pharmaceutical companies to begin doing medical research on cannabis and the legal cultivation of marijuana after decades of violence between drug cartels and authorities.

Pemex workers file corruption charges against union officials, México News Daily. Current and former state oil company workers have filed a complaint against the former secretary general of the Pemex workers union for illicit enrichment.

Pedro Domínguez y Armando Martínez, AMLO encarga una red social ‘sin censura’ para nadie, Milenio. El Presidente instruyó al Conacyt y otras dependencias de su gobierno a buscar un plan para crear una plataforma en la que se pueda garantizar la libertad de comunicación en México.

Cyntia Aurora Barrera Diaz and Maya Averbuch, Mexican President Clashes With Electoral Body Over Briefings, Bloomberg. President Lopez Obrador says he will challenge regulations that could prevent the government from airing his daily press conferences during campaign season, setting up a clash with the country’s electoral body ahead of key midterm elections in June.

Mexico could cancel private prison contracts, says president, Reuters. The powerful U.S. asset manager BlackRock stands among the investors involved in México’s prisons.

Populist Amlo’s tight grip on Mexico finances holds back Covid stimulus, Financial Times. Mexico’s refusal to mitigate the economic impact of the Covid-19 pandemic by boosting public spending is leaving it with the lowest budget deficit among Latin America’s major economies, but that also means its recovery is lagging behind.

Alejandro Hope, Guanajuato, el huachicol y la violencia que no para, El Universal. Es muy probable que Guanajuato sea en 2021 (y por cuarto año consecutivo) la entidad federativa con el mayor número absoluto de homicidios en el país.

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email!

Subscribe!

| Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations. |