Two perspectives on the lessons these two historic events hold for today’s movements.

The Chicano Moratorium – A People’s Demand for Justice

by Bill Gallegos

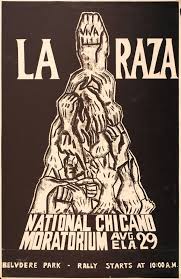

Today marks the 50th Anniversary of the National Chicano Moratorium Against the War, in which 25,000 Chican@s marched through the streets of East Los Angeles to protest the high mortality rate of Chicano soldiers in the Viet Nam War and the oppression and inequality we suffered “at home”, in our barrios and colonias.

The Moratorium was organized by a diverse committee of young Chicano activists that included revolutionary nationalists, socialists and communists, who in many ways represented the growing influence of radical and revolutionary leadership in f the Chicano Liberation Struggle. This leadership was broad and diverse and included the Brown Berets, the Black Berets, La Raza Unida Party, the Crusade for Justice, La Alianza Federal de Mercedes, members of the Communist Party, Los Siete de La Raza, and others.

In this sense, the Chicano Movement was connecting and identifying itself with the Black Power Movement, the American Indian Movement, other radical social movements especially of oppressed people of color, as well as with the anti-imperialist movements taking place at the time in Latino America, Africa, and Asia.

The 1970 Chicano Moratorium was the largest mass action in our history until the massive marches against Proposition 187 in California in the 1990’s. It was a march which rallied youth, adults, students, professionals, academics, small business owners. But in many ways, the Moratorium was most especially a festival of our working class. The overwhelming majority of those at the march were working people, — campesinos, mechanics, janitors, factory workers, domestic workers, food servers, and teachers.

The mass working class support for this march against the Viet Nam War reflected not only the growing influence of radical organizing in our movement, but also that the mass of our people were “sick and tired of being sick and tired”, they were fed up with the way we were brutalized by the police, by the way our lands had been stolen, by the poor housing, poor schools, poor health care, poverty that we suffered in disproportionate numbers, by the continued repression and denigration of our language and culture. The Moratorium gave a massive and powerful voice to our people – Our Fight Is In Our Barrios, Not In Viet Nam.

But the March also brought to light so many other facets of our oppression and struggle: the horrific “push-out” rate from public schools, our persistent poverty, the super-exploitation of our brothers and sisters who toiled in the agricultural fields, the brutality and murder we suffered at the hands of the police, and La Migra, the continued loss of our lands especially in states like Nuevo Mexico, the repression of our language and culture, the denial of our voting rights, and our outrageous under-representation in political office, as well as in the academia, the media, and the business world.

The Moratorium was a peaceful event, but that did not prevent it from being attacked by a massive phalanx of Los Angeles police and sheriffs who waded into the crowd of men, women, children, grandparents, and babies with batons, tear gas, and shotguns at-the-ready. Four people died from that violence on August 29th, including well-known journalist Rubén Salazar, who had taken refuge from the brutal police assault on the march in a nearby cantina, a refuge that did not prevent his murder from a tear gas canister recklessly fired into the establishment.

And as had always been the case when the police, sheriffs, or Texas Rangers, or the Migra murdered our people, no one was held accountable, a familiar tale that continues to be told in barrios throughout California and the Southwest.

It is absolutely essential that we continue to celebrate and commemorate the Chicano Moratorium. We are the keepers of our own history, since our schools and the mass media fail to do so, except in the most minimal or stereotype way. But equally important are the relevant lessons of the Moratorium for our struggle today, when the President of the Untied States characterizes our population as “murderers and rapists”, unleashes an ethnic cleansing campaign against millions of our sisters and brothers, when we are sick and dying at horrendous rates from the Covid 19 pandemic , when the police continue to murder us in the streets, and when we continue to fill the jails and prisons instead of the colleges and universities.

I would argue that the most important lesson from the Moratorium is the need for unity within our movement. If we are going to ever achieve genuine equality, democracy, and our national rights as a people we must find common ground, we must “unite all who can be united” against the white supremacist capitalist system has doubled down on our oppression.

Another important lesson is to prioritize the organizing of our working class. Our working people the overwhelming majority of our community, and are all “essential workers” who suffer the most from our racist society. The liberation of the Chican@ people is absolutely impossible if our struggle does not include the broad participation and leadership of our workers.

Thirdly, the Moratorium taught us to be internationalists. Our march in 1970 was a critical element of the US anti-war movement and contributed to the ending of that horrible conflict. This is a lesson we can learn today as the US government foments golpes in nations like Bolivia, threatens military intervention in Venezuela, continues its blockage of Cuba, and imposes economic and political pressure on Mexico to support its anti-immigrant policies.

The Chicano Moratorium is truly a “fire that will never die” — an inspiration to our continuing struggle for our national rights , for Tierra y Libertad. La Lucha: Sigue … Sigue!!!!

August 29th: Two anniversaries; monumental significance

by Bill Fletcher Jr.

On August 29, 1970 a powder keg exploded when at least 30,000 Chicanos marched in Los Angeles in militant opposition to the US war of aggression in Vietnam. This, initially peaceful demonstration, suffered vicious repression at the hands of the police in what can only be described as a police riot. The events of 8/29/1970, including the deaths and injuries suffered by protesters, shares much in common with the repressive responses of the State we have seen recently in the protests following the George Floyd murder in Minneapolis.

The Chicano Moratorium, as it was known, was much more than about a police riot. It was an act of defiance on the part of masses of Chicanos, and a complement to the rise of the Chicano-led farmworkers movement in California. It was the linking of the Chicano movement—as a historical movement that arose for national self-determination and against racist & national oppression—with a global movement not only against US aggression in Southeast Asia, but a global movement in struggle against imperialism.

The Chicano Moratorium also displayed the fact that the movement against the Vietnam War was not a movement of white college students alone, but was a multi-racial/multi-national movement that had different characteristics depending on within which parts of the population it flowered.

August 29th has an additional meaning. On August 29, 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana, bringing with it close to 2000 deaths and at least $125 billion in damage. While Katrina was technically a natural disaster, the overall disaster was not natural. Disastrous climate change has been increasing the strength and impact of hurricanes, as predicted by climate scientists. Protection for low-lying areas, e.g., New Orleans, has been woefully inadequate, leaving many populations in complete denial and totally unprepared in the face of a major hurricane strike.

But the Katrina disaster was also represented by the immediate aftermath with the removal of much of New Orleans’ African American population—in some cases permanently—and the construction of a neo-liberal “paradise” in the once great city. The elimination of genuine public education along with the termination of teachers, and the gentrification of New Orleans and other parts of the Gulf Coast have represented a racial and class cleansing of the areas, all in the service of a different vision for the country.

8/29 needs to be a moment to remind ourselves that racist and national oppression often plays itself out in different ways depending on the respective history of racialized populations, but it also shares a great deal in common across ‘racial’ boundaries. The violence against the Chicano Moratorium demonstrators failed to provoke the sort of outrage—outside of the Chicano movement—that had emerged in May of that same year when white students at Kent State in Ohio were murdered by the National Guard. The Katrina disaster and the implications particularly for African Americans touched many hearts but failed to mobilize millions into action in response to the neo-liberal rebuilding efforts (much as we have also seen in Puerto Rico in the aftermath of Hurricane Maria).

Both cases share the “otherness” which is branded on the backs of all racialized populations. Suffering and repression may turn many white stomachs but will not necessarily motivate them to action to the extent that the victims of repression and suffering are viewed as ‘lesser’ beings, or worse, suspect populations.

As we face increasing dangers from right-wing irrationalism, a phenomenon going way beyond the antics of Donald Trump, we need to remember these lessons. Resistance and solidarity must be our watchwords, and history must be our foundation.