The weekly newsletter of the México Solidarity Project

May 5, 2021/ This week’s issue

A guest introduction by international solidarity and labor activist Jesus Hermosillo

Back in 1980s Los Angeles, elementary school kids like me had just one occasion — Cinco de Mayo — that focused our attention on something good related to our Mexican identity, something amazing and inspiring that our ancestors had accomplished, something worthy of celebrating. Through Cinco de Mayo, we learned that a ragtag band of campesinos in 1862 had, like superheroes, successfully defended their town of Puebla against the world’s most powerful army, the invading French intent on overthrowing President Benito Juárez.

I would later learn the more complicated truth. Napoleon’s army returned a year later, taking both Puebla and all of México. That army did eventual depart, but largely due to US pressure, not Mexican ferocity.

Another lesser known fact about that first Battle of Puebla: The Mexicans routing the French celebrated by singing the French national anthem, La Marseillaise. An appropriate choice. The common people of France, after all, had risen up against their own repressive monarchy. Both their anthem and the Mexican anthem — only eight years old at that point and not yet widely known — exhort citizens to reach for whatever weapon they can to hold tyranny and imperialism at bay.

So why did our Chicano activist forebears — like Bill Gallegos, who we feature in this week’s Voices — make a holiday out of the Battle of Puebla, a short-lived victory barely remembered today south of the border? In all likelihood, to instill a little pride in kids like me. Their movement won Chicano studies in universities and a bit of Mexican history in public schools, no small victory — even if, like the Battle of Puebla, the enemy returned to attack again. Just a few years ago, remember, a president of the United States labeled us rapists and criminals.

Regardless, the story of Cinco de Mayo imparts a message that bears repeating year in and year out: that dignity lies in fighting for freedom.

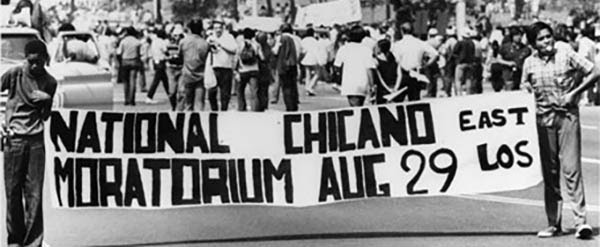

Bill Gallegos spent much of the 1960s and 1970 as a leader in the Chicano movement. Back in those years Chicanos were dying in disproportionate numbers in Vietnam and facing racist attacks and police brutality at home. They built a powerful movement against all that. In 1970, their anti-war/anti-racist protest — the Chicano Moratorium — brought 30,000 people onto the streets for a peaceful march met with teargas, clubs, and bullets. For activists in those years, Cinco de Mayo became a rallying cry for rights, resistance, and self-determination. We asked Bill, a co-editor of our México Solidarity Bulletin, to put those times — and the Cinco de Mayo holiday — in context.

Many people in the United States today see Cinco de Mayo as Mexican Independence Day, but it isn’t. What historical significance does the day have?

Bill Gallegos: Cinco de Mayo — May 5, 1862 — marks the date Mexican troops defeated the invading French army at the Battle of Puebla. After centuries of Spanish rule, México had declared its independence from Spain on September 16, 1810 — the official Independence Day — and threw off Spanish rule in 1821. Then here comes Napoleon III, emperor of France, looking to add México to the French colonial empire. He sent in over 5,000 troops from the world’s most powerful army. They landed in México and set out to march to the capitol of México City. Directly in their path: the city of Puebla, defended by 4,700 poorly armed troops, but commanded by lgnacio Zaragosa, a seasoned guerilla warfare strategist. The French troops charged against the heart of the Mexican defenses. The defenses held. The French lost 1,000 soldiers. The Mexicans only lost 85 men. The Battle of Puebla handed France its first military defeat in 50 years and left the whole world looking at México with new respect.

How did Cinco de Mayo become a rallying cry for the Chicano movement in the US?

Antonio Sanchez from Central Washington University explains that well in The Real Meaning of Cinco de Mayo. In the late 1960s, he notes, Chicano civil rights activists on college campuses throughout the Southwest and California “purposely adopted the Battle of Puebla and May 5 as their day to publicly celebrate” their proud heritage. For the first time, he adds, college campuses heard the cries of “Viva la raza, viva Cinco de Mayo!” That cry amounted to “a bold statement of self-determination” and “cultural allegiance with Mexico,” a “defiant recognition of the accomplishments of the capable Mestizo people of Aztlan.” A new and hopeful Chicano holiday had “emerged triumphantly” from the struggle for civil rights.

How was Cinco de Mayo used to build the Chicano movement?

Cinco de Mayo as a slogan and celebration proclaimed our national pride in full view of the greater US public and opened the door to a larger discussion of our history, including the real meaning of US annexation of México’s northern territories in 1848. People of Mexican/indigenous descent had lived on the lands now in Texas, Arizona, New Mexico, Colorado, and California for hundreds of years and had maintained a culture still rooted in indigenous practices and beliefs.

Our movement developed an analysis that this culture represented a new Chicano Nation, with a unique identity forged by a century of life in the United States under an oppressive racist system. Through this analysis, the Chicano struggle became integrally connected with struggles in México against Yanqui imperialism. We fought not just for equality with white Americans, but for Chicano sovereignty.

Cinco de Mayo is now recognized nationally, even on Hallmark calendars! Do you consider that a victory?

Unfortunately, US alcohol corporations have largely coopted this holiday. They market it as an occasion to get drunk and party, not to celebrate an anti-imperialist victory, much less to motivate the Chicano people’s ongoing struggle against racism and national oppression. They horribly disfigured the holiday into “Drinko for Cinco.” But we still do have authentic celebrations in some communities and college campuses. And we still need to insist that our true history be recognized and honored throughout the US educational system and in popular culture.

Have Chicano activists built solidarity with the people of México?

Yes! Chicanos provided powerful support for the Zapatistas and, more recently, have given support to the Morena Party that swept to victories throughout México in 2018. The right of Chicanos to self-determination in the illegally annexed territories of Aztlan in the US Southwest and the right of México to exercise sovereignty free from US domination have been and will be two parts of the same struggle.

Bruce Hobson has lived and worked in both México and the United States and currently co-edits the México Solidarity Bulletin. We’ve adopted this reflection on Cinco de Mayo from his analysis just published by Liberation Road.

Mexican Culture: Not a Costume

The excitement over the victory against the French in 1862 traveled from Puebla to the West Coast of the United States during the US Civil War. México had abolished slavery when it won its independence from Spain in 1821, and Mexican Americans saw the Puebla victory as a win for sovereignty and democracy and against enslavement and empire. At the same time, México enthusiastically supported the Union, worried that if the Confederates succeeded, Mexicans, non-white people, would also face subjugation.

The significance of Cinco de Mayo for those in the United States was begun by Mexicans living on the West Coast during the US Civil War. Mexicans in the American West also celebrated in hopes that the Union might be victorious and end slavery and racist practices in the United States. They commemorated the Puebla victory with parades, dances, and banquets, part of why the event remains so anticipated in the United States, not in Mexico…

But Cinco de Mayo as many know it now is removed from its original context. The market for alcohol and Mexican food during the holiday has been seized by US capitalism. In the 1980s, US beer companies saw the vibrant Cinco de Mayo celebrations as an opportunity for profit. They’ve associated Cinco de Mayo with drunk white people in sombreros, not the deep history of Mexican culture in the United States. When beer and salsa go on sale on Cinco de Mayo, it is clear that profit is the priority. Taking advantage of a holiday as an opportunity to party erases its cultural significance. Mexicans get stereotyped and marginalized for practicing their culture, others wear costumes they throw away after recuperating from their Cinco de Mayo hangovers.

Recent news reports and commentaries, from progressive and mainstream media, on life and struggles on both sides of the US-México border

Bill Fletcher Jr. and Bill Gallegos, Building Communities of Solidarity, Monthly Review. A powerful interview with Fernando Gapasin, the veteran labor organizer and Chicano activist.

Jorge Gómez Naredo, El nuevo engaño: AMLO “está destruyendo” la democracia mexicana, Polemón. Hay una embestida mediática en marcha que tienen un solo objetivo: hacerle creer a la población que Andrés Manuel López Obrador es un enemigo de la democracia.

Mark Stevenson, Mexican union vote halted at GM plant; vote fixing alleged, Seattle Times. A GM plant in the state of Guanajuato has become a flashpoint in the struggle for labor rights in México.

Nick Corbishley, México’s AMLO Locks Horns With Business Elite As Make-or-Break Elections Loom, Naked Capitalism. AMLO’s political movement, Morena, seems likely to strengthen its grip on political power in the upcoming midterms. And that appears to be the last thing the business elite, both inside and outside México, wants.

David Vine, 175 Years of Border Invasions: The Anniversary of the U.S. War on México and the Roots of Northward Migration, Council on Hemispheric Affairs. Throughout U.S. history, invasions have gone almost exclusively from north to south, not vice versa.

México marks end of last Indigenous revolt with apology, Associated Press. The apology comes amid broader commemorations of the 500th anniversary of the 1519-1521 Spanish Conquest of México.

Demonstrators claim anchored cruise ships are environmental threat, México News Daily. Billionaires from the US and other nations own the cruise ships that steam into international tourist destinations. US and Mexican activists have been organizing against them for years.

The Mexico Solidarity Project brings together activists from various socialist and left organizations and individuals committed to worker and global justice who see the 2018 election of Andrés Manuel López Obrador as president of México as a watershed moment. AMLO and his progressive Morena party aim to end generations of corruption, impoverishment, and subservience to US interests. Our Project supports not just Morena, but all Mexicans struggling for basic rights, and opposes US efforts to undermine organizing and México’s national sovereignty.

Editorial committee: Meizhu Lui, Bruce Hobson, Bill Gallegos, Sam Pizzigati. We welcome your suggestions and feedback. Interested in getting involved? Drop us an email!

Web page and application support for the México Solidarity Project from NOVA Web Development, a democratically run, worker-owned and operated cooperative focused on developing free software tools for progressive organizations.